How we’re financing and producing movies determines who gets to tell the story. And it matters who tells the story.

Schwarze Filmschaffende is a network of Black filmmakers in German-speaking countries, with and without a history of migration. Founded in 2015 as a Facebook group by Marie-Noel N’twa, the organization is committed to equal opportunities and diversity in front of, and behind, the camera. As well, part of their mission is to push for non-discriminatory education at film schools and other German educational institutions. On 17 April 2023, the members of Schwarze Filmschaffende collectively published an Open Letter on the “anti-Black films” Der vermessene Mensch/Measures of Men (Germany), Seneca – On the Creation of Earthquakes (Germany), and Just Super (Norway). The three films had been part of the program at the 73rd annual Berlinale in February. The letter is addressed to the attention of the German Minister of State for Culture and Media; the Chief Executive of the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media; the executive director of Kulturveranstaltungen des Bundes in Berlin; the executive and artistic directors of the Berlinale; and, to the directors of the German Film Academy / Die Deutsche Filmakademie.

The document was copied to over 100 independent European, British and North American film organizations, institutes, and companies, as well as to influential curators and funders, so that their public statement “…should be understood as a call to action by the individuals and organizations placed in cc of this letter. It should call for solidarity and, above all, for support in the fight against racism and discrimination in film. Public discourse on racism and discrimination in film should be encouraged and seen as an opportunity.” The letter can be read, in full, here.

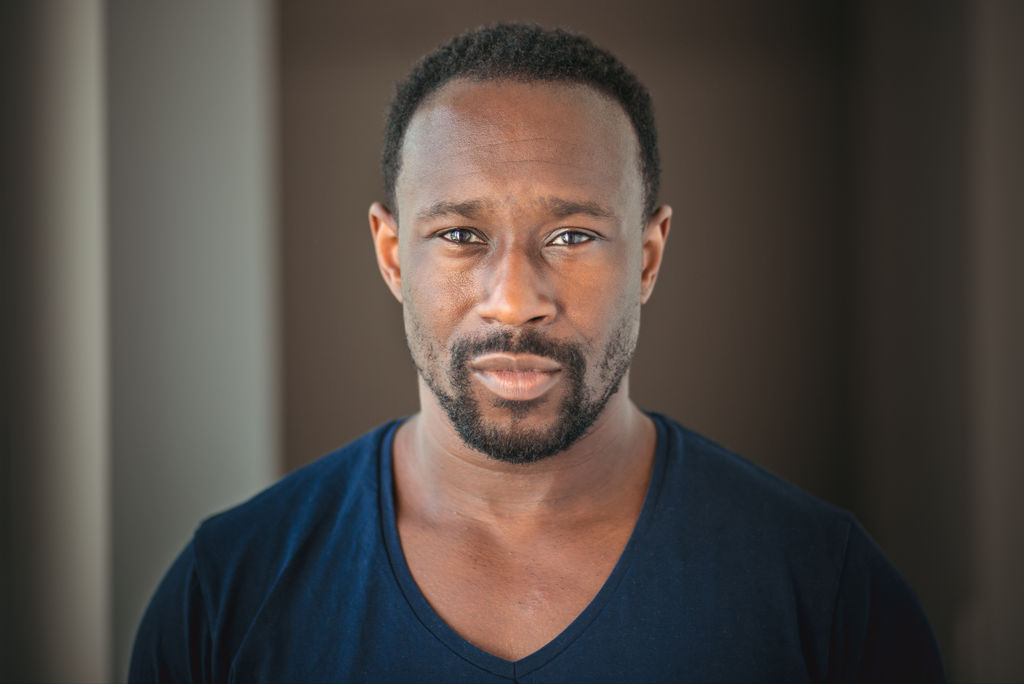

Actor and producer, Jerry Kwarteng, was born in 1976 in Hamburg and has worked in film and television since he was seventeen. Actor and scriptwriter, Marie-Noel N’twa, was born in 1990 in Vienna, Austria, graduating from Film Academy Vienna in acting in 2017. She’s currently writing for a sitcom for ZDF/Network Movie and is also currently writing her first feature film script. Spurred on by the activism that’s been growing in America, starting with the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement founded in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer; April Reign’s 2015 #OscarsSoWhite campaign, a movement that called attention to decades’ worth of neglect and exclusion of non-white entertainment talent at the 87th annual Academy Awards; and the 2020 murder of George Perry Floyd Jr, killed by a police officer in broad daylight in Minneapolis, Minnesota during an arrest – all of it recorded on a mobile phone by a witness and disseminated around the world – Schwarze Filmschaffende means to make an impactful movement in order to fight for more inclusivity in the German-speaking film industry on behalf of all non-white German media professionals. I had the opportunity to speak with these two dynamic and passionate artists and activists in mid-July to learn more.

Pamela Cohn (PC): I’d love to start by having you share some thoughts and inspirations about why you chose to become performing artists.

Marie-Noel N’twa (M-NN): I was very, very shy as a kid. At seven years of age, I was moved to a boarding school in Switzerland and one of the teachers there suggested I try drama class – not to get rid of my shyness, but to be able to be in a space where I could open up and be more myself. That was the best decision ever. It made me realize that there’s a side of me that is outspoken and extraverted. It’s also okay to be quiet sometimes and I found this balance through acting. I knew from that moment on, this was the only thing I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

Jerry Kwarteng (JK): I wanted to become an actor when I was very young; at the age of six or seven I already knew that. I’ve always loved the world of movies because I was a kid who lived through my imagination; that’s where I felt the safest, the most open. I became part of a children’s theatre group, but there, I only got to play roles that I didn’t like, meaning they were always based on my skin color. I grew up with American TV shows of the eighties and nineties and I loved them. I never saw anyone like me on TV in Germany. But on American TV and in the movies, you could see Black people in all kinds of roles, including that of the hero, like Eddie Murphy. In the Beverly Hills Cop films, he was the hero, he was funny and also the smartest guy in the room. Meanwhile, in Germany, I was being cast in the part of a drug dealer, or an immigrant. Directors would tell me that they knew me playing these roles meant that I would have to be taking the piss out of myself. I understand that Black drug dealers exist. But the problem wasn’t just only showing Black people in stereotypical roles. The real issue was that what was never shown was that we are also doctors, lawyers, parents, teachers, etc. What was so baffling and disappointing was the complete disregard for the impact these images have on the German society, Blacks and whites alike.

As a young Black man in Germany, I already had my own identity problems. I grew up in a district of Hamburg where I was one of very few Black people, not really feeling wanted in society. So that combined with what I was experiencing on film sets led me to quit acting. I studied law at university, became a lawyer and moved to Spain. After moving back to Germany, I decided to try acting again because that desire never left me. The industry didn’t change that much in ten years, but I had, and I wanted more. I wanted to create a need in Germany for Black actors just by showing up, by being there, creating an environment where we were able to be seen. To be honest, it was really tough.

PC: Besides wanting to talk about your passion for your artistic and creative work freely, you’ve also chosen to take on the responsibility to re-educate the very industry you want to be a part of – something of course white actors never even have to think about. How did those impulses emerge as you were creating roles and going out on casting calls? As a formerly shy person, Marie, what kinds of things did you have to navigate to step into a leadership role?

M-NN: My story very much connects with Jerry’s because when I graduated from high school, I didn’t start acting right away. Coming from a Congolese household, acting is not considered a job that brings food on the table. [laughing] And so I also studied law for three years in Vienna, but I didn’t finish. I finally found the courage to enroll in acting school. Whilst I was in acting school, I always had the reflection that there wasn’t a representation of people who look like me in Austrian media. I was aware that I was growing up in a very white space. As a child, I always connected to the stories being told, the personality of the characters, so I wasn’t aware of the lack of representation.

When I started acting school, however, I realized much more clearly that I was different and that the roles given to me in classes were going to be similar to the roles that I would get after school. During those three years, I got a lot of projection from my peers and teachers, not in the sense that they were being quote-unquote racist, but in the sense that that’s all they saw in me, the box I was supposed to fit into. I knew I would need to break that box and that there would be something I would have to do for myself in creating those roles. Not just for myself, but also for other Black people who would come after me, to ensure that nobody feels the way I did during a time that should really be all about the art. That’s when I decided to do something about it.

PC: Was Schwarze Filmschaffende formed in part in response to the recent issues that occurred at this year’s Berlinale, specifically as it pertained to the three films in the festival’s program that you challenged? Or had it been founded more in the spirit in which you and Jerry have been speaking about – a space where other Black German-speaking actors could gather in solidarity?

M-NN: Initially, the founding of the organization came from a very personal space. I knew that I could not be the only Black person who wanted to work in film and theatre in German-speaking countries. A friend of mine who was studying with me at the time connected me to a friend of his who was living in Cologne, and she connected me to Jerry. We founded the first Schwarze Filmschaffende as a Facebook group in 2015 and Jerry just invited everybody he knew to join. From there, we just kept growing. I felt relieved and also excited to come together with all these people who had been doing the work, actively trying to push our narrative. That was beautiful to see.

JK: I had realized that just in order for me to do what I wanted to do, I had to go over lots of stepping stones that only apply to non-white people because of the systematic structure in place. I knew that the whole system needed to change, and I had no idea how to do that. What I do know how to do is to network. I knew I wasn’t the only Black actor in German cinema because there had been a lot of Black actors that came before me that had opened some doors. When Marie approached me, it was great because I wouldn’t have ever thought to open up a group or space for Black people. When she contacted me, my first thought wasn’t to create a safe space so much as seeing it as an opportunity to put together other people who look like us for the industry to see that we are here.

When I first started in the business, agencies would tell me there was no work for Black actors in Germany and that I needed to go to the US or the UK. And I thought, but I’m German. I don’t want to go to America where the competition would make it so much harder for me to get work. I was also told, essentially, I wasn’t needed because no one wanted to see me. There were individuals in various departments fighting on their own. But I would be told that while there was a desire to involve Black actors, writers, directors, they just simply couldn’t be found. This made me angry. And that was the point Marie stepped into my life. This was the opportunity to make us visible as professionals so nobody could continue to say they could not find us.

We started to meet so many creative, talented, smart people, and they made this group into something that neither Marie nor I could have imagined. Really, the international impact of George Floyd’s murder gave us the backbone and confidence as a group to start to speak out on not just the three movies cited in the letter, but so many films that used the importance of Black skin to tell a narrative from a strictly white point of view. It’s such a complicated, complex situation. On the one hand, I just want to be an artist. I don’t want to be the one to tell other artists what stories to tell and how to tell them. But it must be understood that the images you transport, that travel the world, are seen in different ways other than your own way of seeing them and the movies we used as examples didn’t seem to be paying attention to that. There are always several perspectives to images, to stories.

What we want to do is be able to articulate how those images affect us, what they do to us as Black people. Being a father, I am very aware of the images about us that are being put into the world. I don’t want my kids or other kids to go through what I had to go through. In thirty years, there should be some progress in this regard. If you never see a wide array of perspectives, you won’t believe you can ever achieve anything because that is the world showing you that you just don’t exist. It’s great to have a dream. But part of our mission is that we want young non-white kids to believe that it’s possible to realize that dream.

PC: As a poet and scriptwriter, Marie, you’re also devoted to the craft of writing your own stories, from your perspective, taking that power of the word and using that to help create the possible world Jerry’s speaking about for yourself and other non-white actors.

M-NN: The idea of writing itself also emerged after acting school. I was fully aware at that point that if I was going to stay in Vienna, the roles that were going to be given to me would never be the ones I wanted to play. I was inspired by actor/writers like Issa Rae and Michaela Coel who decided to write their own stories and put themselves in the forefront of playing those roles as well. So, I thought, okay, with the media we have today being geared towards YouTube, Instagram, all of that, there is a possibility to create stories that are putting Black women and men in the forefront, stories anybody could relate to. At the end of the day, we all go through the same shit. Whilst building a web series [Melanin Scripts, developed and produced with dramaturge Malina Nwabuonwor], I was contacted by an Austrian director who had found our Instagram page and told me how amazing she thought it was and asked us what we needed. She wanted to know what she could do to help. Just this link, this bridge, reminded me exactly why I was doing what I was doing.

When you decide to put yourself out there, to create an image and a connection, people resonate with that, people want to see that. One of the biggest issues I have with the Austrian film industry is that they’ll state that their viewers don’t understand that a Black person speaks fluent German, that their viewers have never seen this. That’s so wrong on so many levels! I continued honing my craft, doing workshops, taking classes, finding a mentor, all to ensure that I bring these stories that are part of my community into the German-speaking industry and to remind people that there’s so much beauty in connecting cultures and ideas through comedy and drama and theatre. There’s so much more than what we grew up with in every sense. It’s important that we create a space for it and allow that space to exist so people can tell their stories. It’s been a struggle sometimes to balance my desire to just tell stories and the responsibility I have to people who have come before and everybody who’s coming after me. But at the end of the day, one flows into the other and at this point, I’m very grateful to be able to write, act and push our narratives into the mainstream media.

JK: I’ve had roles in the past where I was told to speak in an African accent. I would ask what kind and they would say they didn’t care as long as it didn’t sound German [laughter]. It didn’t occur to them that I could be a German who grew up here and just happened to have a different skin color. As Marie worded so well, there can be so much to gain from the perspectives of different cultures in Germany. In my opinion, the lack of those perspectives is a huge missed opportunity. The one-sided display of crime shows, comedies, and historical pieces mainly from the World Wars, is mostly a biased description of the situation. Furthermore, the variety of genres is missing in our country. German movies are told in a very similar way.

For instance, there’s a film from 2018 about a Black girl’s story that takes place in World War Two Nazi Germany called Where Hands Touch by Ghanaian-British director, Amma Asante. This movie was shown all over the world. But not in Germany. In asking some distribution companies why they didn’t bring this film here, I was told no one was interested. However, the only difference in comparison to all the other WW2 movies is her focus on the perspective of a young Black German woman. Things have changed so much due to the various streaming services we have now, as well as the internet. A small group that might be really critical of a film or TV show can sound much bigger than it is. When we wrote this letter, initially, very few people saw it and read it, so our community made it public. I’m so happy to see it’s had the response it’s had and that’s directly due to the internet. Audiences are not the same as they were – spectators want these changes too. It’s just so funny to me that our filmmakers have that strong belief that they think they know what the audience wants. I’m so inspired by French movies, Korean movies, Spanish movies. In France, they connect all the different cultures, which are all French, into one, and that leads to different French perspectives. Even though in Germany we’re making steps forward, there seems to be this struggle of non-white people being accepted as Germans. For some reason, nowadays there is still an explanation required as to why a non-white person is appearing in everyday roles. This is where our group wants to push things.

PC: There is a section in the letter that talks specifically about artistic freedom and the inalienable right to harm, which you alluded to earlier in the conversation, Jerry. It says, in part: “Since we have had many situations of such experiences in the past, we reject the misuse of the term artistic freedom in connection with any forms of racism and discrimination in film, as so-called “artistic freedom”. These cinematic abuses have nothing to do with our humanistic arguments of dignity, preservation and protection against symbolic, psychological violence, but rather are based on a filmic pathology of harm that is regularly perpetrated, maintained and defended by mainly white, cis-gendered men.”

I’d like to talk about this more specifically by referencing Lars Kraume’s Der vermessene Mensch, one of the films you mention in the letter, a film about a real historical event that occurred in the late 1800s, a massacre of an entire generation in the former colony of “German Southwest Africa” that very few people know about. The film is written and directed by a white European male director with a white European male protagonist. In the light of what you’ve been speaking about, would this story, as told in a film, been received differently if it had been directed by a Black African or Black European filmmaker?

JK: Yes, the movie would have been made and received differently if a Black director had made it because it’s all about the director’s need and motivation to tell that story. My interest in a story where Black people are involved is a different perspective than a white person’s and that has to do with very clear emotional restrictions. A white person can never fully understand what a Black person is going through just as I can’t understand fully what a white person is going through, or a woman, or a queer person, for the same reason. But any storyteller needs to be open to criticism as to how they choose to tell a story. A film like Der vermessene Mensch is a political movie. Those movies, by their nature, have a different message than, let’s say, a comedy or something purely for entertainment. If you touch any political topic, you need to know that it’s going to affect a lot of people emotionally and push a lot of buttons. Looking at how funding for films in Germany works at the same time as this rise of right-wing parties in the country could make it even more difficult to show different perspectives in these kinds of movies in the future. It actually presents a very grave danger to restrict the kind of critical movies we are producing.

In terms of a film that presents itself as an historical piece from a certain point of view, I see it as one avenue that can open dialogue. I could understand that a white director wouldn’t dare to tell the story from another perspective. But that director could also work together with someone who does have that perspective. That’s part of what we’re trying to do – to create more accurate and fuller portrayals, particularly in this case where it’s about something, as you said, that hardly anyone knows about. This massacre wasn’t taught in school. I didn’t know about it until I was an adult. These are the films that travel all over the world, maybe to schools and universities, where young people are being presented with this very narrow perspective, one guy who, in the movie, is trying to do the “right thing”. He struggles and he fails. I don’t understand this motivation not to show the vulnerability and responsibility for what happened. I don’t know when or if this topic is ever going to be tackled again, and by whom.

If there was, or is, a Black filmmaker that wants to also tell this story, I really doubt he or she would get the same kind of funding as this well-known German white director did. That’s why it’s so important to say something about this film and that they missed a very important perspective about the slaughter of a whole generation of people. The African perspective could have been included, but it wasn’t.

How we’re financing and producing movies determines who gets to tell the story. And it matters who tells the story. Even with the best of intentions, one person cannot fully understand what it feels like to walk in the shoes of all of the characters portrayed.

M-NN: I’m in complete agreement. There is a feeling in the German-speaking industry, particularly at this moment where there is the acknowledgment that we have to make more diverse movies with more diverse characters, that has been present since Black Lives Matter and George Floyd’s murder. There is this pressure to avoid shame or possibly the complete cancellation of a project. But this is not the message we’re sending out. Our message is one of inclusion, cooperation. However, if a Black person wants to tell this same story, they will not get the same funding, as Jerry mentioned. This is clear in the example of Amma Asante’s film that we mentioned before – a film about a Black girl’s story during the Second World War that played everywhere except Germany and Austria. This needs to change!

PC: There is this growing global imperative on behalf of various colonialist nations, whether they be perpetrated by Germany, the US, South Africa, Australia, Russia, Israel, on and on, to just blinker the historical line to only include certain “missteps” framed in a certain way – in other words, a very controlled and exclusionary narrative. This makes me think that the work you’re engaged in has a much broader purpose than just portrayals in film and television and the funding landscape. These cultural pathologies run deep.

JK: In the case of Germany, everything is run very bureaucratically so the purpose is not to exclude someone or exclude certain people. It’s just the nature of how bureaucracy works. This makes things here move very slowly. And in adding more diversity, it’s just perceived as a sort of checklist. Maybe we can have a Black gay person in a wheelchair in this role, so that’s three boxes ticked. [laughter] It even took America such a long time, but I’m inspired by how many films made recently have flipped the coin. More movies from a Black perspective have emerged and not just big historical films. This is missing in Germany. We are creating these stories and making these films from different perspectives here but hardly anyone is paying attention.

My deepest hope is that all of these things we are focusing on now in Germany and Austria and trying to change will catch up to what’s happening in other places. This is what keeps other modes of progress from moving forward and we really do need to get out of our own way.

M-NN: I’m pragmatically hopeful on what the next ten, twenty years have to offer, especially when it comes to Schwarze Filmschaffende and, more widely, to the German film industry.

Right now, we are in the midst of the battle. It’s important that whoever reads our Open Letter, as well as this interview, realizes that it is a battle that we cannot fight on our own. It’s important that we have allies, others who feel strongly about all this who are willing to open up and say something and join the cause. You are more than welcome.

Despite our name, this does not mean we’re only open to Black people. It’s something we all have to change together. I really do hope more people get involved.

And I also hope that more Black people won’t be afraid to step into this industry, bringing their personalities, their stories, and, most importantly, their talent. We need you. We want you. We want to see you.

Pamela Cohn is a Helsinki-based critic, writer, film & video curator, story structure consultant, and festival moderator. She’s the author of Lucid Dreaming: Conversations with 29 Filmmakers(OR Books, New York & London, 2020), and co-producer and host of The Lucid Dreaming Podcast: Conversations on Cinema, Art & Moving Image. http://www.pamelacohn.com/