I have climbed a tree, I see beautiful apples I can’t reach yet, but I am closer than I

would be if I climbed down… I have to keep climbing, even at the risk of falling.

–from the diary of Libuše Jarcovjáková, September 1986

When I first watched Czech director Klára Tasovská’s film on Libuše Jarcovjáková, it resonated in all kinds of ways. I thought about what author Jhumpa Lahiri talks about in her 2015 book, In altre parole / In Other Words, a book I’m currently reading in Italian and English on facing pages. The memoir is about Lahiri’s arduous journey to think, write and create in another language not her own, one where she is a perpetual outsider, a foreigner, someone relegated to the margins. She writes: “The frame defines me, but what does it contain? All my life I wanted to see, in the frame, something specific. I wanted a mirror to exist inside the frame that would reflect a precise, sharp image. I wanted to see a whole person, not a fragmented one. But that person wasn’t there. …I saw something hybrid, out of focus, always jumbled. I’m afraid that the mirror reflects only a void, that it reflects nothing. I come from that void, from that uncertainty. I think that the void is my origin and also my destiny. From that void, from all that uncertainty, comes the creative impulse. The impulse to fill the frame.”

I’m Not Everything I Want to Be consists solely and entirely of black and white stills from Libuše’s photographic archive made over the course of a lifetime, accompanied by her first-person voiceover narration. The film feels like a huge gift to female artists everywhere and is a triumph of a challenging, but completely fitting, form. What emerges is an incredible homage to the film’s protagonist and her life, a life that oftentimes displayed a trajectory where so many convergences of the political and personal collided in surreal and evocative ways. No matter the ways in which we endeavor to push our lives uphill, accidents of fate always intervene and change our course out of nowhere. The makers of this film figured out how to illustrate this in Libuše’s story, making it feel so lifelike.

Klára graduated from the New Media department at Academy of Fine Arts in Prague and from the Documentary Film department at FAMU. Her mid-length documentary essay Midnight (2010) was screened at several international film festivals and her feature-length début Fortress (2012) directed together with Lukáš Kokeš, the producer of I’m Not Everything, was awarded Best Czech documentary at Ji.hlava IDFF 2012. It also competed at CPH:DOX 2012 and was nominated for the LUX PRIZE in 2013. Klára’s last film, Nothing Like Before, also co-directed with Lukáš, premiered at IDFA’s First Appearance Competition in 2017.

The 71-year-old Libuše is the author of 2016’s “Black Years” and teaches photography to young aspiring artists in Pilsen and Prague. She’s also currently working on a Ph.D. She wrote: “I have indulged in out-of-the-ordinary life experiences. I have become a part of different social groups – probably because of my empathy – which is an important part of my personality and gives me an endless source of visual stories to tell. I took volumes of images which turned out to be a kind of continuous subjective documentary with an apparent autobiographical impact. The collections flow quite naturally from one to the other, with the next subject just upstream.”

A few days before they departed Prague for Berlin for the film’s world premiere as part of Berlinale 2024’s Panorama program, Klára, Libuše and I talked about the watershed moment in 2019 that saw Libuše’s first major retrospective in Arles; the arduous task of curation when faced with a lifetime’s worth of material; the trust, friendship and understanding the small film team built with their amazing protagonist; and the very weird tendency on the part of others to compare Libuše’s life and art to American portraitist and slide show maven, Nan Goldin.

Pamela Cohn (PC): Klára, how long of a creative and production process was this from its conception? What was the backbone, in your opinion, of this particular collaboration with Libuše?

Libuše Jarcovjáková (LJ): I’m curious too about this question of how long it took. [laughter]

Klára Tasovská (KT): I’ll say it was about four years, the beginning of the production work happening right before the Covid pandemic in 2020.

LJ: From my side, I would say that this collaboration with Klára was all about absolute trust. Around 2019 [following the Arles exhibition], I began to get many offers from various film directors about wanting to do a documentary film. In none of these individuals did I feel I would have a partner. With Klára, it felt right from the very beginning. It took several months for me to decide to trust her and her team in order for me to be able to give them all the material I had. From our earliest talks and the questions that she was asking me, the process had a fluidity and trustworthiness to it. I felt I was in good hands with her. She understood the story that was there.

KT: Libuše didn’t really know anything about me, nor had she seen my films. But she said to me that it was her very good intuition that informed her decision to work with me and that she was really excited to go through her archives in order to discover something new about her works through the making of this film together, that this material would be given a context. Selecting and curating all the boxes of diaries and the thousands of negatives that I had in my home was so exciting for me, a new world to explore. I enjoyed it very much.

PC: Was the idea in place for you from the very beginning, to make a feature film solely through the use of Libuše’s photographs?

KT: As I mentioned, right in the midst of the development phase, the pandemic started. And since Libuše was stuck at home, she started scanning some negatives from her time in Japan, going through these photos for the first time forty years after first taking them. She was also discovering, or re-discovering, some of her own work. She photographed everything in her life along with all these self-portraits, as well as the diaries she’s kept her entire life. I saw this very complex story in these materials almost immediately and decided that this film would consist only of this personal archive. It would be a story of Libuše’s world through Libuše’s eyes. This idea, of course, was very difficult to explain, a feature film consisting of still photos was scary, somehow, for various producers or television commissioners. At East Doc Platform, I was pitching the project and while there, I was assigned two mentors, editor Maya Daisy Hawke, and producer Iikka Vehkalahti. They were both incredibly supportive about this approach. From a practical point, no shooting was really possible anyway during that time and so that was to our advantage because we could say that we truly already had all the material we needed to make a film. With the encouragement of Maya and Iikka, we had confirmation that it could work.

PC: You’ve said that, for you, Libuše embodied the larger questions of what makes a life story, even though her life diverged constantly, forcing her to improvise in order to survive. It’s like she possessed an intuitive or second sense about the circumstances of a place and time where pretty big things were happening. But she used those sometimes really tough moments to reflect upon how she could be a better artist, a stronger person, to allow herself to be more persistent in her own vision about what she wanted her life to be. That’s all reflected so beautifully in the film, embedded in every frame.

KT: Yes exactly, for me, she does embody the ideal female protagonist, one that speaks about such universal themes through her very personal conflicts. She herself seemed to solve these dilemmas years ago, ones that are still prevalent today for so many artists, so many women: working in male-dominated societies, the theme of motherhood, sexuality. It’s the same reason I love the books of Annie Ernaux or Sheila Heti’s 2018 autobiographical novel “Motherhood”. They share very personal preoccupations that I also saw in Libuše’s materials.

LJ: I have to say, though, that it’s difficult to know how much of this was a conscious process for me. I’ve always been a natural outsider, someone who simply wasn’t able to deal with any model of life presented by an outside authority or social convention. Both my grandmother and my mother were independent women. But I also observed the fate of my mother who was always in the shadow of my dominant father. They were both painters, but he stole all the creative space in the household, and she was the one that worked to support all of us. I knew that wouldn’t be my fate. They were open people, not really conventional, and for me that was the only way to survive. It informed my decisions not to have children, not to collaborate with any regime in any form, even when it came to a working life. What I’m saying is that it was natural, intuitive, not necessarily things I thought about too deeply. I never felt myself to be a person who would fight against a “man’s world”; that wasn’t really my concern. I was how I was, and it wasn’t that important to me about how to fit into the society around me. Frankly, sometimes I’m surprised at my own attitudes from that time and how it was possible for me to live how I did. When I see it in the film now, it’s surprising to me the life I lived. But it happened.

PC: Libuše, you’ve stated that, “What’s strange is interesting, but what is most strange is most interesting.” In line with this statement and in accordance with your dedication to teaching, do you work to instill in your students this same idea or spirit about the way you frame things? Not necessarily the technical aspects of photography, but the ways in which they’re opting to encounter the world around them and their place in it through a camera lens. I see this also in Klára’s own directorial spirit that lives in that place of searching for inspiration and the right road to travel.

LJ: There’s one word that encompasses all of the ideas you’re putting through, Pamela, and that’s: humanity. To have empathy, to remain open, to constantly observe the cosmos around you, to be as tolerant as possible. This is what I want to share with my students. The visual work of catching the sense of the world around you is the most important thing. For me, I can be most present in my own life through the work I’m doing. That presence is so complex because that presence happens through process. The visual narrative presented is, in some ways, more important than what might be happening, or where I happened to be, what was going on in my life at the time.

PC: Take us through your initial processes, Klára.

KT: I can say that from the beginning, I did want to tell Libuše’s story chronologically because for me, it was important to show her personal development, the changes in her personality over the course of her life. The diaries themselves helped me figure out the plot points, which became chapters. Then I could develop each chapter, each chapter consisting of times when Libuše decided to change her life, her circumstance, to leave something behind to look for something new, most of the time starting from zero, even starting over in her native culture upon returning to Prague from Tokyo, for instance. These are what made the major movements and shifts in the narrative. It took a really long time to work this way, making constant decisions about what to include. Luckily, I worked with editor Alexander Kaschcheev, who is also a sound designer. He edited Daria Kaschcheeva’s short film, Daughter from 2019, which won a student Oscar, and Daria’s 2023 short Electra, which premiered in Cannes. Sasha has so much empathy and we sat together for almost two years, pretty much full-time, in the editing room. [Kaschcheev is credited as a co-writer on the film.] There were about seventy thousand photos to manage and organize and connect with my notes from Libuše’s diaries, which seemed to work on paper. At the time, the voiceover was my own recorded voice, to save time and try the best solutions. But the content of the narration often didn’t work with the images that well, so we went through the diaries again and again to fine the best way to connect the diary selections to the narration of the images. After the first year working like this, we shared the rough cut with Libuše to refine the selected notes, and then we started to work with her in the studio so that she became the narrator of her own life story.

Part of the selection process during the edit was searching for those photos that had movement at their core, as well as her presence, because she is our guide to her story. I wanted to make a personal story, not the larger historical one, to see everything through her eyes. I wanted to stay away from any notion of a slide show or just choose photos because they were the most beautiful ones, The brutal honesty of her life and the opening of her personality, discovering hidden parts of her identity and expressing who she was through her art was crucial for me. I wanted to offer an essay, of sorts, on female life and its struggles through her story.

PC: It was a curator writing on your work, Libuše, who first put forth this comparison of your life and work with that of American photographer, Nan Goldin. On some level, it’s a simplistic, short-hand way to reference something – I’m not sure what – but I’m not convinced at all by this comparison. [Libuše laughs] Goldin, of whom I am a fan, came from a very privileged background, in fact, and hardly did she come of age in the midst of a repressive regime, quite the opposite. Goldin also did have a good amount of public notoriety in her early career. To my mind, the two of you come from different planets entirely. Your entire life has been a push against this kind of cavalier categorization, so to refer to you as the “Czechoslovakian Nan Goldin” is misleading, to say the least. What do you think?

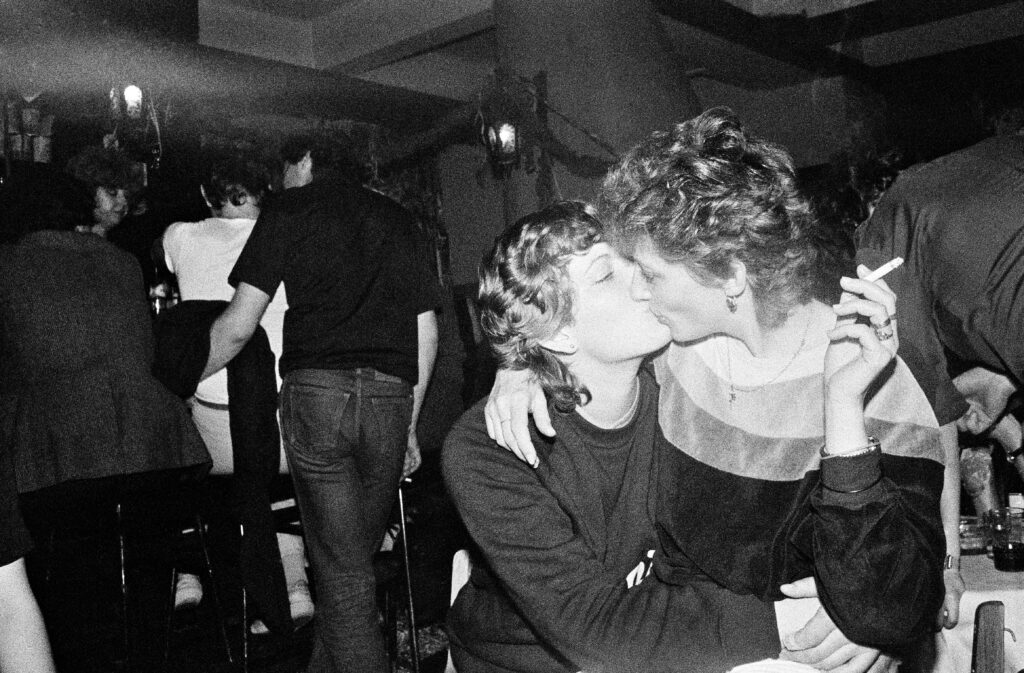

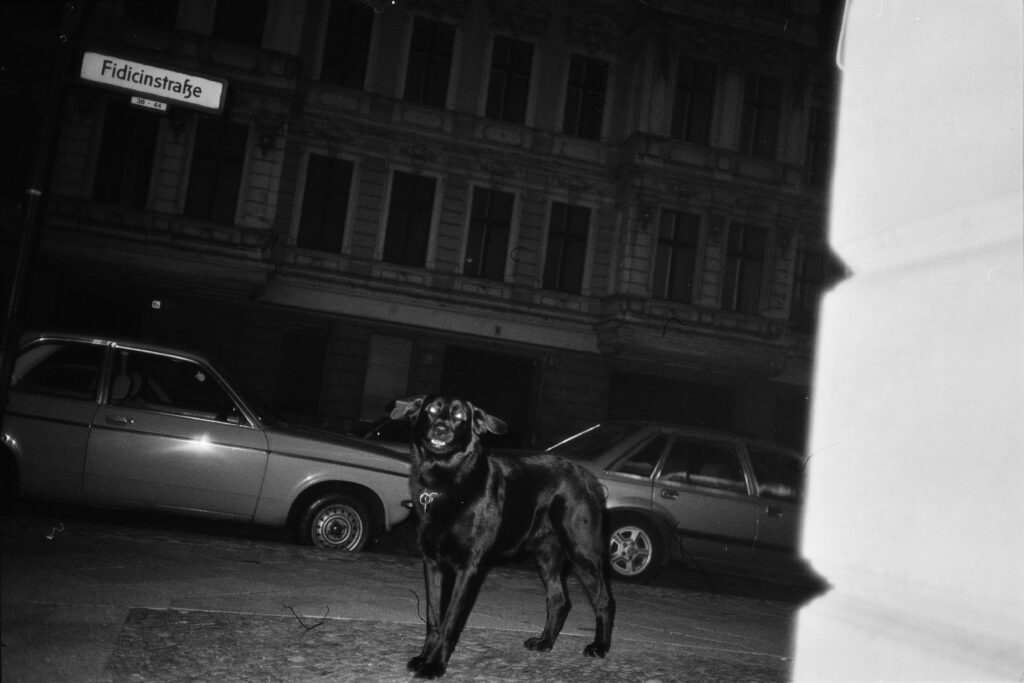

LJ: I definitely agree with you. Like you, I love the work of Nan Goldin as well, but I wasn’t really familiar with who she was and the work she was doing until about ten years ago. Oddly, we were in Berlin during the same period, around 1985. I didn’t meet her, but we probably lived within kilometers of one another. I was working as a chambermaid at Hotel Intercontinental and I was the only person in the world who knew that I was a photographer; I was irrelevant to anyone else. And she was already successful. I don’t feel any important connection between us. I mean even technically it’s a different world. She made snapshots that she had developed at a drugstore and never set foot in a darkroom. I worked with East German black and white film. It was very difficult to even buy color film and it tended to be very bad quality. Our lifestyles maybe had some similarities – her world was filled with drugs, mine with alcohol. We both documented our most intimate relationships and circle of friends. So yes, there are similarities, but our styles are completely different. I don’t have any need to fight against the comparison even though it’s simplistic, but that’s my opinion on it.

PC: What are the distinct advantages of being “discovered” at such a stage in your life? This archive can now be shared so widely, more so than you maybe ever imagined. Were there points in your life where you longed for more recognition for your work? Did you have moments of frustration around that?

LJ: I think there’s the advantage of really enjoying this recognition now and in the past few years. Yesterday, I did a lecture at the photographic school in Prague for young students, ages fifteen to twenty-four. It was a huge auditorium and I saw that the young people there really understood the work and that it did provide some inspiration for them. I’ve known my whole life that I am a photographer and it made sense. Living through it all without recognition or publicity was normal. I wasn’t particularly frustrated about that.

There was frustration, however, when I came back from Berlin and started to teach here in the beginning of the 90s. Then, there were many photographers sharing their archives and getting some renown, exhibitions, and so on. I was just nobody, no name. I thought it was a pity that I wasn’t more a part of what was going on in those artistic movements. But I loved teaching and was very involved and engaged with that. I’m not a very good self-promoter and I didn’t go to the right parties and openings. The beginning of making that name actually came from my students. The first exhibitions happened around 2008 to 2010 with my students as the curators. I really didn’t share too much of my work with them, but they discovered it. This film will have my work seen more widely and will create more interest. So that’s lucky for me because there are so many great photographers and artists that never see this kind of luck.

These excellent people started coming to me and wanted to collaborate – Klára, Lukáš, and my curator, Lucie Černá, who made the book and exhibition of my work at Arles called “Evokativ” in 2019. I have people around me now helping me to articulate my voice in a very clear way. These outside approaches offer deep empathy and understanding towards me and there’s so much respect in how they work with my material. It shows me something new and important about my own work and that inspires me. I like a quiet life and not to be on the stage too much. My parents, as artists, were not very successful and are obscure, almost forgotten. They didn’t have the opportunity to be in the public eye like I am experiencing. I feel some debt towards them, but I also have never had the energy to push their work. My grandfather was also an unknown painter. But what is a “successful” life for an artist? I don’t really know what that means.

KT: Libuše was waiting so long for the kind of big exhibition that was in Arles, but the year after that, the pandemic started, and she was sort of stuck again. She and Lucie were preparing some other exhibitions, but of course everything stopped. I hope this film also helps to get those other things that were already in motion happening again.

I, too, wanted to be a photographer but my parents were very unhappy about that [laughs]. But I did study art, and a lot of my friends were photographers. It was through them that I knew about the work of Libuše, but I didn’t know about her story until this Arles exhibition in 2019. Commissioners from Czech television came to me with this idea to make a film about her, which made me so happy. I found myself in her story somehow.

LJ: And I found such a quietness and peace during this whole process, knowing I was in good hands with the whole team and I’m so glad that it’s happened this way, that my story in the way it’s told in the film can speak to a younger generation of photographers, as well as to make a bid for more tolerance. Maybe just a little bit.

Pamela Cohn is a Helsinki-based critic, writer, film & video curator, story structure consultant, and festival moderator. She’s the author of Lucid Dreaming: Conversations with 29 Filmmakers(OR Books, New York & London, 2020), and co-producer and host of The Lucid Dreaming Podcast: Conversations on Cinema, Art & Moving Image. http://www.pamelacohn.com/